You’re probably here because you want to learn how to finish a song. Never has a music career been launched where the artist never finished songs.

Why? Because music isn’t listened to in part, it’s listened to as a finished product.

So if you want to grow as a producer, for your own sake or for building a career, finishing tracks is non-negotiable.

But it’s hard, Sam! My ideas aren’t good enough and I don’t know where to take them!

Well, let’s get into some strategies that you can use to finish music faster, easier and better than ever.

Note: this blog post is an excerpt from my book, The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity.

New to music production? 🧑💻

Watch our Free Masterclass on how to learn electronic music production the smart way (without months of confusion & frustration) 👇

WHY NOT FINISHING IS BAD

Ideas, if not fully developed, don’t mean much in the long run.

No one wants to listen to a loop. They want to listen to something that’s finished; they want a complete song.

It’s easy to think that because you’re coming up with a bunch of ideas, you’re getting better as a producer. This, of course, isn’t always true. If you’re coming up with a ton of ideas but never seeing them through, then you’re avoiding the difficult but necessary process involved in completing a song. It’s through that process—through moving the needle—that you really become a better producer.

The non-finishing habit

It’s easy to build this habit. Most of the time, we don’t know we’re falling into it (I imagine that’s generally the case with bad habits!)

It starts off innocent. You’re working on a project, and you discover a new, exciting idea.

So you put the current project aside to work on the new idea, telling yourself that you’ll revisit the original project later.

As you’re working on the new idea, you encounter a challenge. Maybe the track doesn’t flow right. Maybe the melody isn’t as good as you thought it was.

You decide to set that project aside “for now,” and work on a new project. After all, you don’t want to be wasting precious time.

As excuses are made, the cycle repeats. You develop the habit of abandoning projects. It becomes your default mode, and before long your hard drive begins to grow full of unfinished ideas.

Recommended: Dawphobia: Why You’re Not Making Music As Much As You’d Like

Three reasons why not finishing tracks is a bad thing

Before we look at how to finish tracks, it’s important to understand why finishing them is so crucial.

1. It stems progress

Many producers fail to finish tracks because of a weakness or lack of skill in a particular area.

For instance, you might struggle with mixing or using effects, so you jump ship when it comes to the mixdown stage; or you might struggle with the arrangement, so you start a new project whenever it comes to arranging your ideas.

Often, the lack of completion that producers face comes from a (subconscious or even conscience) fear of embracing difficulty. Not always, but often.

On the other hand, the producer who consistently finishes tracks develops their skill-set evenly.

Why?

Because to finish a track, you need to go through all the stages: composition, arrangement, mixing, and everything in-between. You have no choice but to work on areas that challenge you.

2. It crushes credibility

You can post as many memes as you like on your Facebook artist page, but if you don’t release music consistently, people won’t take you seriously.

Even if you’re a new producer with little social reach and you’re not really focused on building your brand, it’s still an issue. The people in your inner circle will quietly perceive you as less driven or motivated and won’t feel as inclined to invest time and effort in helping you.

Not being able to finish tracks also means you can’t deliver in situations where it’s essential.

For instance, if I asked you to collaborate with me on a track, and you didn’t pull through, what impression will that leave on me? Likewise, if a vocalist or instrumentalist asked you to produce a track for them (paid project) and you couldn’t deliver, how would you feel?

3. It’s less fun

Sure, finishing music is challenging, but it’s also fun. There’s a feeling of intense satisfaction one gets when exporting the final version of a track.

The less you have this feeling of satisfaction—the less you finish tracks—the more mundane and frustrating music production becomes, and the more likely you are to want to give up and watch Netflix

Furthermore, by not finishing tracks, you begin to tell yourself that you can’t finish tracks. You get stuck in a feedback loop. A feedback loop that features a toxic combination of little output and feeling sorry for yourself.

START STRONG

One of the main deciding factors of whether or not you finish a song is how smoothly the first few hours go.

With some projects, as I’m sure you’ve experienced, the first few hours fly by with ease. You’re completely immersed in the process, and you generally finish 60-80% of your track in the first session.

When this happens, the likelihood of finishing the project is much higher than when the first few hours are stressful, tiring, and broken up.

There are two reasons for this.

The first is that you build a ton of momentum when the first few hours go smoothly, and it’s much easier to work on a track that’s 80% finished than a track that’s 30% finished.

The second reason is that you tend to associate negative feelings towards a project where the first few hours spent on it weren’t enjoyable.

So, given that, how do you ensure that you have a great first session? How do you start strong?

1. Slay the dragon

I arrived in Amsterdam two days before Amsterdam Dance Event.

I was staying with my friend Budi Voogt (co-founder and director of Heroic Recordings), and as soon as I got off my flight we headed to his office. It was the afternoon, so everyone was still working.

He showed me around, and I noticed a whiteboard with the word “Dragons” on it that had a task for each team member written underneath.

Budi explained what they were. Unfortunately, I can’t remember exactly what he said (I’d been awake for 36 hours – I can’t sleep on planes), but it was something along the lines of…

“A dragon is the most important task that needs to be done. Each of us has a dragon for the week, and the goal is to slay the dragon.”

Productivity gurus have been using illustrations like this for a while now. Even Mark Twain once said, “eat a live frog first thing in the morning and nothing worse will happen to you the rest of the day.”

When you’re working on a song, it’s crucial that you slay the dragon first. If you put it off, things are only going to get more difficult and you’ll feel less inclined to finish the track because there’s a dragon waiting to strike.

So what’s the most important thing?

There’s no one answer. It depends entirely on the style of music you’re making and what you’re good at.

If you’re making a trance track, the most important thing might be writing a melody. The longer you avoid writing a melody, the harder it will be to finish. If you’re making a drum and bass track, the most important thing might be the drums, so you work on them first.

Let’s be honest though, you probably know deep down what the most important thing is. It’s that thing you keep wanting to avoid.

Note: The most important thing is not always the most difficult thing. If it comes down to it, you should prioritize the most important thing over the difficult thing, but address the difficult thing soon after.

2. Have a long first session

Slaying dragons takes time. Starting strong takes time.

Typically, your first session is the longest. It’s where you make the most progress. It’s where energy and excitement are high and you can easily enter the state of flow.

To start strong, you really need to give yourself a decent chunk of time. I recommend at least 90 minutes. It may sound like a lot, but you need to capitalize on the rare excitement and creative flow that comes with a new project.

“I have to add that my workflow is pretty fast in the first hours into my projects. That is because I have an idea I want to write down. So usually in the first hour or two the whole “skeleton:” of the track is down. A rule of thumb is that if you don’t like your track by the first studio session, you can’t really expect to improve on it in the following sessions. Unless you have some sort of skill that enables you to pick up projects and completely morph them to your liking.” — Naden

Don’t quit if you’re excited

It’s easy to be working on a project, get excited, and then close up shop for the day feeling satisfied.

Of course, ending a session at peak excitement is one of the worst things you can do. It’s easy to tell yourself “This track is great! I can’t wait to come back to it tomorrow.”

But when you do eventually come back to it, it’s rare that you feel the same level of excitement you had earlier.

So, when you’re excited, capitalize on your excitement. Sometimes this means staying up a little later, or having lunch two hours late. It will require some effort and concentration, but you’ll thank yourself for it later.

3. Set a first session goal (optional)

This is an optional strategy because it can be harmful.

Setting objectives for production sessions is a no brainer in the later stages of a track, but in the beginning, an objective can inhibit creativity because it forces you to think more sequentially and logically. It can also add unnecessary pressure.

However, if you set a broad but measurable goal for your first session, it can focus your mind wonderfully and help you make massive progress in the first few hours.

Your goal might be to finish the full arrangement. A goal as broad as that won’t inhibit creativity, whereas a goal like “write a 16-bar melody and counter-melody,” will because it dictates where your track should go (all songs have an arrangement, but not all songs have 16-bar melodies with counter-melodies).

Tip: It’s a good idea to set a next session goal so you can keep the momentum rolling through the following sessions. At the end of the first session, set a specific objective that you want to focus on during the next session. This one can be less broad.

New to music production? 🧑💻

Watch our Free Masterclass on how to learn electronic music production the smart way (without months of confusion & frustration) 👇

Iteration not inspiration

“This is the difference between professionals and amateurs. Professionals set a schedule and stick to it. Amateurs wait until they feel inspired or motivated.” — James Clear

The common belief in the electronic music production community is that you need to be inspired to create music and that if you aren’t inspired, you simply have creative block and should wait until the next wave of inspiration hits you.

If that were true, everything would rely on luck. Don’t feel inspired? Tough.

Fortunately, creativity doesn’t come down to inspiration alone. Common sense tells us that inspiration and motivation are both unreliable. If we want to be successful creatives, we have to look deeper.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying inspiration is bad. There’s nothing better than feeling inspired to work on a track, or feeling extremely motivated and driven to do something. But it’s rare, and it shouldn’t be relied on.

In short, if you rely on inspiration, you’ll give up quickly, feel a lack of satisfaction, and fail to have high output.

So what can you do?

Iterative production

When you have inspiration, capitalize on it. But when you don’t feel inspired, realize that that is the norm and don’t let yourself get disappointed.

If you’re used to making music when you feel inspired, how do you make it when you’re not feeling inspired?

You use something I like to call Iterative Production.

Iterative production is a method that, once practised and understood, will make a huge difference to your workflow and ability to start and finish tracks.

It involves starting with something extremely simple, and turning it into something satisfactory through a series of small additions and adjustments (iterations).

A brief example

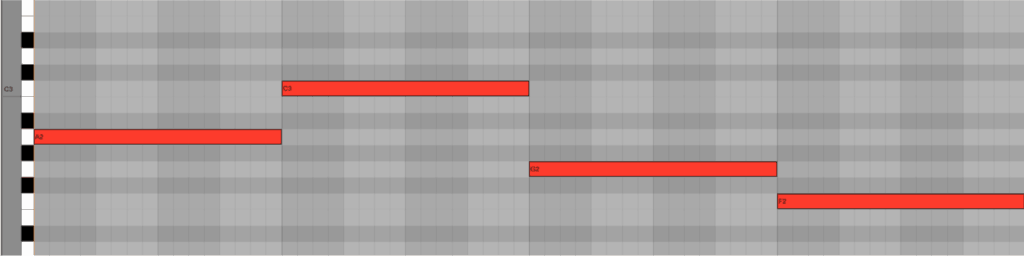

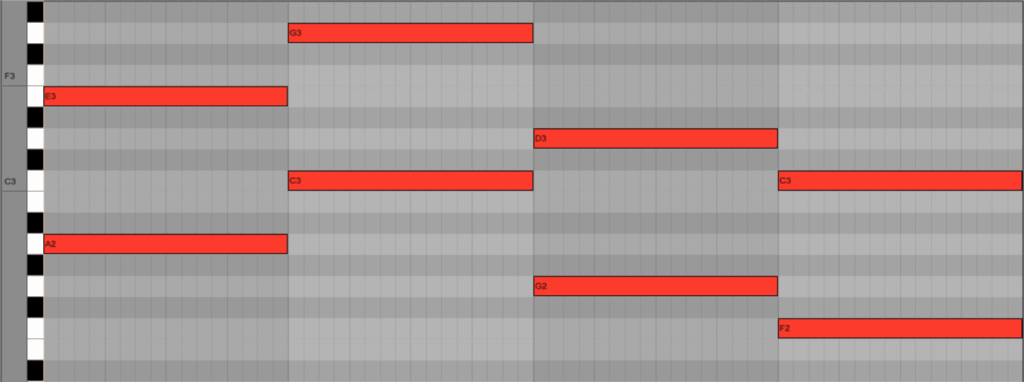

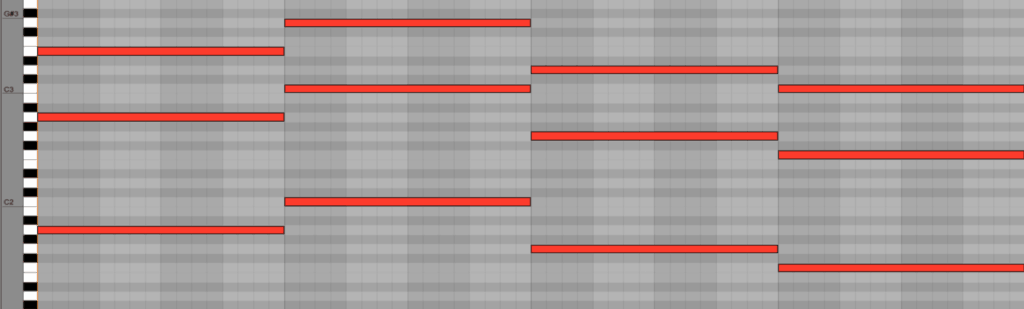

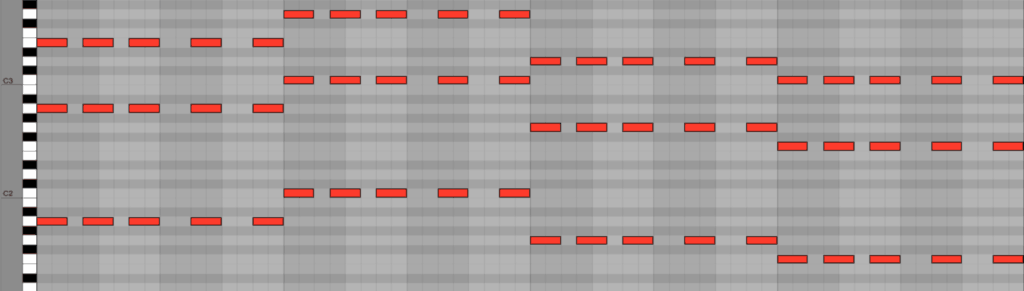

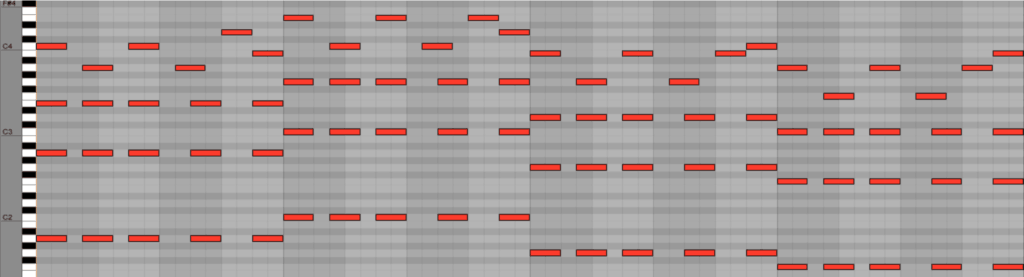

Let’s start off with a simple 4-note bassline in the key of A natural minor:

Easy, right? The key here is to reduce friction right from the beginning. You don’t need inspiration to create a 4-note bassline.

Next, let’s add a 5th to each note.

Again, nothing difficult.

Next, let’s double the root note to add some body to the sound.

Now we can chop this progression up to create a rhythm.

Still easy? You bet.

At this point, we might add in a melody over the top (this is the most difficult part—use your ears).

Our end result isn’t the most amazing melody in the world, but it’s something, and we achieved it through a series of small, easy steps.

DEADLINES AND ACCOUNTABILITY

There are no tools more powerful in the creative person’s arsenal than accountability and deadlines.

These two are almost always linked, with the exception being that although deadlines can be self-imposed, you can’t really be accountable to yourself.

Let’s first look at the power of accountability and how it relates to finishing tracks.

The three layers of accountability

The first layer is P2P (person-to-person) accountability and it’s what most people think of when they hear the word accountability.

The second layer is public accountability which is generally stronger than the first layer.

The third layer is reliant accountability and is stronger than the first and second layer.

Let’s unpack these in detail.

P2P accountability

Person-to-person accountability is one of the most common forms of accountability and also the easiest to set up.

It can be as simple as asking a friend or someone you know to keep you accountable on a certain goal or habit.

For instance, you might tell one of your producer friends that you’re going to finish one track per week and that you’d like them to message you at the end of each weak to ask if you’ve finished your track for the week.

If you want to install some sort of accountability into your workflow, then doing it this way is a great start.

How to do it well

If finishing music is your problem, then you should centre your accountability goal or habit around that.

Finishing one track per week is a good benchmark, but you may prefer to organize it on a track-by-track basis with a more specific deadline (you tell your friend that you’ll finish your current project by a certain date).

It doesn’t really matter who you pick to stay accountable to, as long as they’re willing to help out and flick you a message from time to time.

They also don’t have to be a producer. However, it does help if the person you’re staying accountable to is a creative of some sort. That way they’re a bit more understanding and sympathetic—as they know how hard it is to finish things—and may offer some encouragement along the way.

Of course, you should opt for another producer if possible. They can share tips, you can rant to them, share your feelings, do a producer-counselling session together… you get the idea.

That’s all well and good, Sam. But how do I actually approach someone and ask if they can hold me accountable?

If they’re a friend, you already know what to do.

If they aren’t, use the template below. Modify the style, tone, and formality based on your relationship with the person.

Hey [name],

How are you? Hope you’re well.

I’ve been reading through a book on workflow and creativity for electronic music producers and there’s a chapter on finishing music, which is something I’m currently struggling with.

One strategy that the author recommends to help finish tracks is to find someone to stay accountable to someone so there’s a little more pressure to finish music.

I think this would be a helpful thing to do, and you came to mind first. It’s really simple: my goal is to finish one song per week, and at the end of that week I’ll message you with a link to the completed song. You don’t have to listen to it, of course, it’s just for me to show someone that I’ve finished it.

All I ask is that if I don’t message you at the end of the week, you contact me and ask what’s up.

Would this be cool?

– [Name]

If they don’t know that you produce, simply use the above template but include something like this at the beginning:

Hey [name],

Not sure you know this, but I’ve been spending the last few weeks/months/ years making electronic music.

Why am I telling you this? Well I’ve been reading…

Public accountability

Public accountability is less personal but can be more powerful because you have to look good in front of more than one person.

One example of public accountability that worked well was the August Loop Challenge we ran last year.

Participants would spend exactly 20 minutes on an 8-bar loop every day, and then upload their loop to a Soundcloud group. We had 50 people contribute. Not all of them made a loop every day (some of them quit), but there was a core group of people that saw the challenge through.

A few of those people got in touch with me personally to tell me that if it wasn’t for the public nature of the Soundcloud group, they’d have given up in the first week.

A more recent example of public accountability is the Deep Work Challenge that Budi Voogt and I have started.

The challenge arose because we wanted to spend more time doing focused work. We tried P2P accountability, but it didn’t work too well. At least, not for me. Budi managed fine. He’s a machine.

So, we got talking and came up with the idea to publicly log how many hours of deep work we did per day. We set up a Google Spreadsheet which you can find here.

At the time of writing this, we have six people logging their deep work hours in the spreadsheet. It works well because there’s an element of competition. There’s also the fact that my name is at the top and anyone on the internet can see how much work I’m doing.

How to do it well

There’s a bit more involved in public accountability than there is in P2P accountability, but the initial time investment pays for itself tenfold.

The best way to do it, in my opinion, is to set up a public webpage. A Facebook post announcing that you’re going to finish one track per week isn’t as permanent as a webpage declaring your objective. It’s also easier to update your webpage weekly to reflect whether you’ve achieved it or not.

Alternatively, you could use a shared Google Sheet like Budi and I are doing for the Deep Work Challenge.

By the way, it doesn’t really matter whether anyone’s viewing it or keeping tabs on you. You can just pretend they are. The main reason it works so well is that people can visit that webpage or spreadsheet and you don’t want it to show that you haven’t finished anything.

The Facebook Group Method

I haven’t tried this. It’s something that popped into my head while writing the last sentence (caffeine is awesome), but I’m sure it would work.

Create a Facebook group with several people that want to finish more music (ask for their permission BEFORE you create the group – it’s rude to just add people).

Then, create some sort of schedule. For example: on Sunday evening every week, you post an update where people can link to their finished track. If there are ten people in the group, there should be ten comments on that update assuming everyone’s done the work.

Note: There’s no reason why you can’t use P2P and public accountability at the same time, but it’s probably overkill to do so.

Reliant accountability

Reliant accountability is the least common of the lot, which is unfortunate because I believe it’s the most transformative tool for lasting change in any area of life.

It involves setting up an accountability program in a way where the other person or persons rely on you, and you on them. If you don’t do the work, they get put at a disadvantage.

A non-music example of reliant accountability from my life came to fruition a few weeks ago.

A friend of mine who lives roughly 100 meters down the road is joining the air force. He has to work his way through a six-week fitness program to pass the requirements.

Obviously, it involves a lot of running, and I’d mistakenly mentioned to him a few weeks earlier that I wanted to run more (I didn’t, but it felt like a cool thing to say). So, he asked me if I was keen to start running with him.

We run together every day. If I don’t show up, I’ve let him down, and vice versa. If it was just me following the schedule, I’d come up with a myriad of excuses for why I shouldn’t go for a run that day.

So, how can you apply this kind of accountability to music production—more specifically, finishing tracks?

The first and most obvious answer is collaboration, but that’s not the most feasible option (we also cover it in detail during chapter six).

You have to get creative. Here are two methods I recommend:

The show & tell method

At the end of every week, you have a chat with your accountability partner (someone who’s trying to do the same thing as you: finish a track every week).

During this chat, you share anything and everything you’ve learned from finishing your project for the week. It might have been a new technique, a cool sample pack you’ve come across, whatever.

If you get to the end of the week and haven’t finished a track, you can’t share valuable information, right? I mean, you can, but you won’t help yourself (or your partner) if you aren’t honest about your progress.

The project swap method

Warning: Only do this with someone you trust.

At the end of each week, swap project files. Do this for learning purposes, to see

how the other person has put things together and mixed their track.

This is more cumbersome and involved than the show and tell method, but it’s also more foolproof because you can’t really lie. If you send over a project file that is blatantly unfinished, the other person will be disappointed. He or she can’t learn as much.

Deadlines

Deadlines help you focus. There’s a famous and slightly morbid quote from Samuel Johnson that reads…

“When a man knows he is to be hanged…it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

Of course, self-imposing a deadline for a song to be finished by a certain date isn’t going to have as much an impact as being told you’re going to die in a few weeks, but it still does something.

The mistake many producers make when setting deadlines is they make them too long. Your deadlines should be as short as possible, and then some.

There’s an old adage written by C. Northcote Parkinson that states: “work expands so as to fill the time available for its completion.”

If you think you can finish a song in one week, set the deadline for four days. If you think you can produce an album in a year, set the deadline for eight months.

The common objection to setting short deadlines is that they result in lower quality work. This is true, to an extent. Obviously, if you tried to make an album in one week it wouldn’t turn out great, but eight months? That’s plenty of time.

In fact, shorter deadlines can actually result in better work. You realize time is of the essence, and you focus more deeply and do better work.

New to music production? 🧑💻

Watch our Free Masterclass on how to learn electronic music production the smart way (without months of confusion & frustration) 👇

THREE MORE STRATEGIES FOR FINISHING MUSIC

1. Lower your standards

Having high standards for your work is important. All artists have high standards.

But high standards are not helpful when you can’t finish any music. In fact, they can actually stop you from finishing music: you work on something, it doesn’t reach your (unreachable) standard, and so you flip over to something new.

Don’t mistake high standards for perfectionism. Perfectionism kills progress.

The first thing you must do if you want to re-build the habit of finishing music is to lower your standards.

It’s difficult to lower your standards. It’s such an odd thing to do, and what if you lose your high standards?

You won’t. The key here is to lower your standards until you can finish music consistently.

One thing that helps you lower your standards temporarily is to not think about releasing your work or making it public in any way, shape, or form. As soon as you think about how your track will be received by the public, or your peers, there’s a pressure that’s added.

That pressure forces you to bring up your standards. It’s a good pressure under normal circumstances, but when you can’t finish anything, it’s poison.

So, make the decision to not release anything for a few weeks. Commit to it. If you do make something great, release it, but make sure there’s no pressure.

2. Work fast and carelessly

High standards become an issue because we overanalyze what we’re doing. We listen to something and think that it’s not good enough. We pick holes in it and focus on the minor issues that most listeners might not even notice.

But when you work fast—so fast that you’re slightly careless—you don’t have time for that. You don’t have time to pick holes in what you’re doing or to focus on the minor issues.

Working fast forces you to make decisions immediately. When writing a chord progression, instead of asking yourself, “how can I make this the best chord progression?” You ask, “Is this good enough?”

If it is good enough, you move on to the next thing.

Now, working carelessly is a problem when you’ve built the habit of finishing tracks. You want to put effort into your craft; give it time, and think about it. But it’s key when you can’t finish anything.

Work carelessly because your focus is not to make something good, it’s to actually finish something. It doesn’t matter if it’s bad. Remember, most creative people create more bad art than they do good art.

3. Lower the friction

If you possess an exceptionally bad case of non-finishing, it’s likely that you’re having trouble at each stage of the production process.

Perhaps you struggle to come up with ideas and develop/arrange those ideas.

If this is the case, the best thing you can do is lower the friction and make it as easy as possible to finish something.

One way to do this is to model another track. Not remake it necessarily, but model it.

You can copy its structure, general instrumentation, and use your own composition and ideas. It’s okay if you steal a fair amount from the existing track, (it’s quite hard to make an exact copy of another track anyway).

When you do this, a strange thing happens. You forget that you’re modelling another track because you come up with your own idea that’s so captivating you lose yourself in it. The track makes itself, you just simply used the model track as a launchpad.

Another way to lower friction is to use construction kits.

WHAT?! CONSTRUCTION KITS?! NEVER!

Yes. If you use a construction kit to make a song and don’t add anything original, then you release it and call it your own, I have no respect for you. That’s not creative at all.

However, if you use construction kits purely for the purpose of getting into the habit of finishing, then they’re brilliant. Use as many loops, samples, and construction kits as you like. Make it as easy as possible to finish tracks. Just don’t release ‘em.

As you start to build the habit, do a few more things on your own and use less construction kit elements. Before you know it, you’ll be finishing tracks that are made up almost entirely of original elements.

New to music production? 🧑💻

Watch our Free Masterclass on how to learn electronic music production the smart way (without months of confusion & frustration) 👇

What’s Next?

With an array of new strategies in your toolkit, finishing tracks will in time become a breeze. But music production is all about workflow and creativity, and finishing tracks only works if you have the whole picture.

If you want to develop a comprehensive system for finishing music consistently, check out the full version of my book, The Producer’s Guide to Workflow & Creativity.